Arthur William Harmer

b. 1899, d. 20 February 1958

Last Edited: 2 Mar 2025

- Birth*: Arthur William Harmer was born in 1899 at Coltishall, Norfolk, England.

- Marriage*: Arthur William Harmer married Hilda Emmeline Mann on 28 June 1924 at Colchester, Essex, England.1

- Death*: Arthur William Harmer died on 20 February 1958 at Colchester, Essex, England.2

- Admon*: Administration of Arthur William Harmer was granted on 1 May 1958 at Ipswich, Suffolk, England.2

Family:

Hilda Emmeline Mann b. 23 Dec 1900, d. 1970

- Marriage*: Arthur William Harmer married Hilda Emmeline Mann on 28 June 1924 at Colchester, Essex, England.1

Citations

- [S244] Website "Ancestry" (http://www.ancestry.co.uk/) "Essex Record Office; Chelmsford, Essex, England; Essex Church of England Parish Registers."

- [S422] National Probate Calendar, England & Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995. (https://www.ancestry.co.uk/).

Ellen Redman

Parents:

Father: Henry Redman

Last Edited: 1 Jan 2020

- Ellen Redman was the daughter of Henry Redman.

- Marriage*: Ellen Redman married George Stevens, son of Edward Stevens and Mary Ann Rampton, on 15 July 1877 at St Peter, Brighton, Sussex, England.1

- Married Name: As of 15 July 1877, her married name was Stevens.

Family:

George Stevens b. 26 Nov 1854

- Marriage*: Ellen Redman married George Stevens, son of Edward Stevens and Mary Ann Rampton, on 15 July 1877 at St Peter, Brighton, Sussex, England.1

Child:

Mabel Stevens+ b. 1 Oct 1889, d. 13 Aug 1970

Citations

- [S244] Website "Ancestry" (http://www.ancestry.co.uk/) "Ancestry.com. England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013."

Thomas William Bebbington

Last Edited: 29 May 2011

Family:

Child:

Amanda Joyce Bebbington+ b. 8 Dec 1922, d. 31 Aug 2023

Sarah Barber

b. 24 August 1739

Parents:

Last Edited: 15 Oct 2021

- Baptism*: Sarah Barber was baptized on 24 August 1739 at Tonbridge, Kent, EnglandB, both parents named.1

- She was the daughter of Richard Barber and Elizabeth (?)

Citations

- [S388] Website "FamilySearch" (http://www.familysearch.org/) ""England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975", database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N6KS-L47 : 22 March 2020), Sarah Barber, 1739."

Thomas James Tratt

b. circa 1864

Last Edited: 1 Jan 2014

- Birth*: Thomas James Tratt was born circa 1864 at Clerkenwell, London, England.1

- Marriage*: Thomas James Tratt married Teresa Murrell, daughter of Philip Murrell and Charlotte Evans, on 16 October 1889 at Register Office, Steyning, Sussex, England.

- Occupation*: Thomas James Tratt was a watchmaker in 1891.1

- Residence*: In 1891 Thomas James Tratt and Teresa Murrell lived at 10 St Georges Road, St Pancras, London, England.1

Family:

Teresa Murrell b. 1863

- Marriage*: Thomas James Tratt married Teresa Murrell, daughter of Philip Murrell and Charlotte Evans, on 16 October 1889 at Register Office, Steyning, Sussex, England.

Child:

Thomas Tratt b. 1890

Citations

- [S71] 1891 Census for England "RG12 piece 118 folio 158 page 3."

Mary Barber alias Nynne

b. 29 March 1598, d. 1633

Parents:

Father: George Barber alias Nynne b. c 1558, d. 1627

Mother: Elizabeth Godsell b. 21 Dec 1561, d. 1638

Mother: Elizabeth Godsell b. 21 Dec 1561, d. 1638

Last Edited: 30 Mar 2024

- Baptism*: Mary Barber alias Nynne was baptized on 29 March 1598 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, surname recorded as Ninne.1

- She was the daughter of George Barber alias Nynne and Elizabeth Godsell.

- (Witness) Will: Mary Barber alias Nynne is mentioned in the will of Henry Aderoll alias Skinner dated 6 July 1612 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.2

- (Witness) Will: Mary Barber alias Nynne is mentioned in the will of George Barber alias Nynne dated 18 January 1617 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.3

- Death*: Mary Barber alias Nynne died in 1633 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.

- Burial*: Mary Barber alias Nynne was buried on 14 December 1633 at St Denys, Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, recorded as Barber alias Nunne.4

- Anecdote*: Admon: 1635: Appeared personally Mr. William Awcock, notary public and procurator for John Barber als Nyn natural and legitimate brother of Mary Barber als Nyn late of Retherfield deceased and renounced administration of the goods and chattels of the said deceased .5

Citations

- [S103] Transcript of the Parish Register of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, (ESRO: PAR 465/1/1/1).

- [S361] Will of Henry Aderoll alias Skynner of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, made 6 Jul 1612, proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 2 Nov 1613. (TNA: PROB 11/122/389).

- [S113] Will of George Nynne als Barber of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, made 18 Jan 1617, proved in the Archdeaconry court of Lewes, 26 May 1627. (ESRO: PBT/1/1/20/40A).

- [S443] Rotherfield St Denys, Burials and MIs, undated, Rotherfield, Sussex (http://www.stdenysrotherfield.org.uk/familyhistory.htm).

- [S362] Letters of administration of the estate of Mary Barber of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, granted by the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 1635 (ESRO: W/B6/219).

William Barber alias Nynne

b. circa 1535, d. 1548

Parents:

Last Edited: 10 Aug 2016

- Birth*: William Barber alias Nynne was born circa 1535 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.

- He was the son of John Barber alias Nynne and Joan (?)

- Death*: William Barber alias Nynne died in 1548 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.

- Burial*: William Barber alias Nynne was buried on 1 March 1548 at St Denys, Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, "son of John Nynde."1,2

Citations

- [S103] Transcript of the Parish Register of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, (ESRO: PAR 465/1/1/1).

- [S443] Rotherfield St Denys, Burials and MIs, undated, Rotherfield, Sussex (http://www.stdenysrotherfield.org.uk/familyhistory.htm).

George Barber alias Nynne

b. circa 1554, d. 1555

Parents:

Last Edited: 7 Mar 2015

- Birth*: George Barber alias Nynne was born circa 1554.

- Death*: George Barber alias Nynne died in 1555 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.

- He was the son of John Barber alias Nynne and Alice Farmer.

- Burial*: George Barber alias Nynne was buried on 6 January 1555 at St Denys, Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, recorded as "George, son of John Nynde" which would normally indicate he died a young child. The date also fits perfectly with John and Alice's marriage. However, there is a chance that this could be a son of the previous generation, John and Joan, as their son William's burial in 1548 also says "son of John".1,2

Citations

- [S103] Transcript of the Parish Register of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, (ESRO: PAR 465/1/1/1).

- [S443] Rotherfield St Denys, Burials and MIs, undated, Rotherfield, Sussex (http://www.stdenysrotherfield.org.uk/familyhistory.htm).

Elizabeth Barber

b. 29 December 1647, d. 1667

Parents:

Last Edited: 24 Mar 2022

- Baptism*: Elizabeth Barber was baptized on 29 December 1647 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, Mother's name not given.1

- She was the daughter of John Barber alias Nynne and Mary (?)

- Death*: Elizabeth Barber died in 1667 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB.

- Burial*: Elizabeth Barber was buried on 23 December 1667 at St Denys, Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, "daughter of John Barber."2

Citations

- [S23] Online Index to Baptisms, 1538 onwards, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, http://www.sfhg.uk/, ongoing project,.

- [S388] Website "FamilySearch" (http://www.familysearch.org/) "Film: 1067279; Image: 275."

William Barber

b. circa 1645, d. 1705

Parents:

Father: Thomas Barber alias Nynne b. 15 Apr 1610, d. 1663

Mother: Joan Primmer b. 3 Mar 1615/16, d. 1699

Mother: Joan Primmer b. 3 Mar 1615/16, d. 1699

Last Edited: 24 Mar 2023

- Birth*: William Barber was born circa 1645 at Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB; speculated.

- He was the son of Thomas Barber alias Nynne and Joan Primmer.

- Anecdote*: Although William's baptism has not been found, he is likely to be the son of Thomas Barber and Joan Primer/Primmer. Thomas and Joan married just as the English Civil War (1642-1660) was about to start. The Burwash parish register records the birth of their first child Mary in 1639 but there is then no record of other children until 1652 in the Ticehurst parish register. They would certainly have had children in this period which is notorious for missing or poorly kept parish records. William is almost certainly a son of Thomas for the following reasons:

1. Thomas is likely to have named his first son William after his father.

2. When William married he is noted as "of Ticehurst" and Deborah is "of Burwash".

3. Thomas was employed as a servant of Zebulon Newington (stated in Zebulon's will of 1635) and is known to have connections to Burwash (some of his children were baptised there). The Newington family property, Witherenden, lies midway between the villages of Ticehurst and Burwash.

4. Thomas himself was baptised at Burwash.

Thomas Barber's connections to Ticehurst and Burwash coincide with William's connections to Ticehurst and Burwash, stated on his marriage record (William of Ticehurst, Deborah of Burwash), and strongly suggest that he is the son of Thomas Barber alias Nynne of Ticehurst.

Finally, William's will made in 1705 names his brother Thomas which is consistent with him being the son of Thomas and Joan as they had a son Thomas. - Marriage*: William Barber married Deborah Manser, daughter of Christopher Manser and Anne Byne, on 6 February 1671/72 at St Mary's, Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB, Deborah of Burwash; William of Ticehurst.1

- Marriage*: William Barber married Margery May on 20 February 1698/99 at Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB, William is a widower and Margery is a widow.1

- Occupation*: William Barber was a linen weaver in 1702.2

- Will*: William Barber left a will made on 26 August 1702 at Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB.3

- Will/Adm Transcript*: Will of William BARBER, Linen Weaver of Ticehurst, 1705

(ESRO: PBT 1/1/46/40B)

Made: 26 Aug 1702

Proved: 13 Jun 1705

Familysearch: Film: 1885947; image: 582

In the Name of God Amen the twenty sixth day of August in the year of our Lord Christ one thousdand seven hundred & two x x I William Barber of Tisehurst in the County of Sussex. Linen Weaver being sick and weake of body but of sound & perfect minde and memory, praise be given therefore to Almighty god do make and ordaine this my present Last will & Testament in manner and form following, (that is to say) first and principallyI commend my soule into the hands of Almighty god, hoping through the merrits death and passion of my Saviour Jesus Christ to have full and free pardon of all my sins and to Inherit everlasting life, and my body I commit to the earth, to be decently buried at the discretion of my Executors hereafter named, and as touching the disposition of all such temporall estate as it hath pleased Almighty god of his unspeakable goodness to bestow upon me I do give and dispose thereof as followeth

Imprimis I do give and bequeath unto Margery my now wife the sume of fifteen pounds of lawful money of England to be paid to her within six months next after my death; by my Executors: and Also I do give and bequeath unto my said wife all such goods and household stuff as was her own before our marriage, and moreover my will and minde is that shee the said Margery my wife shall have her dwelling in my house wherein I now live the terme of one whole year next after my death

Item I do give and bequeath unto William Barber my son my working shop and all the wast [waste] grounds that doth belong to the said shop scituate lyeing and being neere unto my dwelling house in Tisehurst aforesaid: Item I do give and bequeath unto the said William Barber my son; and unto Mary Barber my daughter, too each of them a silver spoone; and all the linen that is now in a Chest standing by my bed side equally to be divided betweene them the said William & Mary after my death.

Item All the Rest and Residue of my personall estate moneys goods and household stuff whatsoever and wheresoever (not before willed or bequeathed) I do give and bequeath unto William Barber my son, and unto my three daughters: (that is to say) Elizabeth now wife of Robert Nokes; Deborah now wife of John Jeffery and Mary Barber; all my said goods equally to be divided between them (that is to say) share and share alike of all such moveable goods as I am possessed of and have at the time of my death: which is not before willed or bequeathed And I do desire that my body after my death to be buried privatly in the Churchyard of Tisehurst by my Executors: And I do hereby give unto Mr Swayne the minister of the parish Ten shillings of lawfull money for to preach my funerall sermon the next sabboth day after my buriall to be paid to him by my Executors.

Item I do hereby make and ordaine William Barber my son, and my aforesaid three daughters ye said Elizabeth, Deborah and Mary, full and sole Executors of this my Last Will and Testament. And I do nominate & appoint Thomas Barber my Loving Brother to be overseere of this Will for to assistmy Executors heerein and I do give unto him Ten shillings for his paines.

And I do hereby Revoke disanull and make void all former Wills & Testaments by me heeretofore made, & decalre this to be my Last will & Testament: In Witness whereof I the said William Barber have hereunto sett my hand and seale.

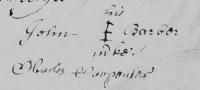

Signed William Barber his X mark

Signed Sealed & published

In the prsence of us.

Will Swayne

Urcilla Thomas

Mary Swayne

Thomas Fowle

13 Junii 1705 ………. [Probate in Latin]

Tho. Whalley Sur

Transcribed by Geoffrey Barber, 24 March 2023

[ ] Transcriber’s note or addition. - Death*: William Barber died in 1705 at Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB.

- Burial*: William Barber was buried on 30 April 1705 at St Mary's, Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB, "weaver."2

- Probate: His estate was probated on 13 June 1705 at Archdeaconry of Lewes, Sussex, England.

Family 1:

Deborah Manser b. 29 Oct 1648, d. 1686

- Marriage*: William Barber married Deborah Manser, daughter of Christopher Manser and Anne Byne, on 6 February 1671/72 at St Mary's, Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB, Deborah of Burwash; William of Ticehurst.1

Children:

Elizabeth Barber+ b. 2 Dec 1672

Jane Barber b. 7 Feb 1674/75, d. 1687

Deborah Barber+ b. 23 Oct 1677, d. 1760

William Barber+ b. 27 Feb 1680/81, d. 1738

Mary Barber b. 16 Mar 1683/84, d. 1724

Jane Barber b. 7 Feb 1674/75, d. 1687

Deborah Barber+ b. 23 Oct 1677, d. 1760

William Barber+ b. 27 Feb 1680/81, d. 1738

Mary Barber b. 16 Mar 1683/84, d. 1724

Family 2:

Margery May d. 1703

- Marriage*: William Barber married Margery May on 20 February 1698/99 at Ticehurst, Sussex, EnglandB, William is a widower and Margery is a widow.1

Citations

- [S24] Index to Marriages, 1538-1837, Compact Disc SFHGCD003, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, 2008.

- [S25] Online Index to Burials, 1538 onwards, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, http://www.sfhg.uk/, ongoing project,.

- [S1086] Will of William Barber of Ticehurst, Sussex, England, made 26 Aug 1702, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 13 Jun 1705. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/46/40B).

John Barber

b. 13 April 1651

Parents:

Last Edited: 23 Mar 2023

- Baptism*: John Barber was baptized on 13 April 1651 at Rotherfield, Sussex, EnglandB, Mother's name not given.1

- He was the son of John Barber alias Nynne and Mary (?)

- Anecdote*: Certificate of Conviction DYK/1047 - 10 Mar 1677 (East Sussex Record Office): Records that Isaac Ford of Frant, labourer, came before William Dyke, Justice of the Peace, and declared that on 19 Feb 1677 John Barber hunted does in Eridge Park, belonging to George, [12th] Baron Abergavenny. John Barber confessed. William Dyke sent a warrant to the Constable of Rotherfield hundred to levy £20 from his goods, which were insufficient for distress. John Barber was committed to the House of Correction for 6 months hard labour.

This could be:

John Barber bap. 1651 Rotherfield, son of John and Mary (would have been age 26).

John Barber bap. 1652 Ticehurst, son of Thomas and Joan (would have been age 25).

John Barber bap. 1663 Ticehurst (would have been age 14).

Given that it occurred in Frant I feel that it is more likely to be John son of John and Mary who we know lived in Frant. - Marriage*: John Barber married Mary Fry on 22 April 1695 at Withyham, Sussex, EnglandB.2

- Anecdote: On 25 May 1696, a John Barber was a juror in a coroners inquest in Frant. Not sure if this is the same John Barber though - needs more investigation.3

- Anecdote*: This marriage and children is speculation. Baptisms for Withyham only start at 1700 but there are no Barbers. I am not sure I have the right John Barber either. It could be the John Barber bap. 30 May 1663 at Ticehurst, son of William Barber, or the John Barber bap. 14 Nov 1652 at Ticehurst, son of Thomas Barber (who was buried in Rotherfield 1663). More research required.

Family:

Mary Fry d. 1701

- Marriage*: John Barber married Mary Fry on 22 April 1695 at Withyham, Sussex, EnglandB.2

Children:

Citations

- [S23] Online Index to Baptisms, 1538 onwards, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, http://www.sfhg.uk/, ongoing project,.

- [S24] Index to Marriages, 1538-1837, Compact Disc SFHGCD003, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, 2008.

- [S284] R F Hunnisett, "Sussex Coroners' Inquests 1688-1838", Sussex Record Society, First Edition (2005) "Case No 445."

Mary (?)

d. 1662

Last Edited: 10 Aug 2018

- Marriage: Mary (?) married John Barber alias Nynne, son of George Barber alias Nynne and Elizabeth Godsell, circa 1646 at Sussex, England.

- Married Name: As of circa 1646, her married name was Barber alias Nynne.

- Anecdote*: John's wife has been identified as Mary purely on the burial in 1662 which says "Mary, wife of John Barber, Retherfield", as the mother's name is not given on any of the children's baptisms. However, it is possible that Mary was a second wife as there is a marriage of John Barber to Joan Coarde on 16 Sep 1645 at Burwash. A Joan Goorde/Goarde/Gourde was baptised 30 Sep 1627 at Barcombe, daughter of Thomas. Another Joan Gord was baptised 30 Oct 1625 at East Grinstead, daughter of Henry and Margaret. These two would appear to be the only possibilities in the SFHG baptism index. While it is possible that Joan Coarde/Goard was John Barber of Rotherfield's first wife (the marriage date fits well with the children's births and no other family has been found for them), there is a burial of a John Barber on 23 Jan 1646 at Warbleton which could also account for him. There is also the marriage of John Barber and Margaret Comber on 21 May 1644 at Buxted which would also have to be a contender.1,2

- Death*: Mary (?) died in 1662 at Frant, Sussex, EnglandB.

- Burial*: Mary (?) was buried on 20 June 1662 at Frant, Sussex, EnglandB, recorded as "Mary, wife of John Barber, Retherfield."3

Family:

John Barber alias Nynne b. 12 Feb 1602, d. 1667

- Marriage: Mary (?) married John Barber alias Nynne, son of George Barber alias Nynne and Elizabeth Godsell, circa 1646 at Sussex, England.

Children:

Elizabeth Barber b. 29 Dec 1647, d. 1667

William Barber b. 23 Sep 1649

John Barber+ b. 13 Apr 1651

Mary Barber b. 4 Jan 1654/55

Richard Barber b. 4 Mar 1659/60

William Barber b. 23 Sep 1649

John Barber+ b. 13 Apr 1651

Mary Barber b. 4 Jan 1654/55

Richard Barber b. 4 Mar 1659/60

Citations

- [S23] Online Index to Baptisms, 1538 onwards, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, http://www.sfhg.uk/, ongoing project,.

- [S24] Index to Marriages, 1538-1837, Compact Disc SFHGCD003, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, 2008.

- [S122] Transcript of the Parish Register of Frant, Sussex, England, 1544-1881 (ESRO: PAR 344/1).

Samuel Theobold

b. 7 March 1618/19, d. 1694

Parents:

Last Edited: 19 Feb 2025

- Birth: Samuel Theobold was born in 1618/19 at Benenden, Kent, England.

- Baptism*: Samuel Theobold was baptized on 7 March 1618/19 at St George, Benenden, Kent, England, (KHLC: P20/1/A/1.)

- He was the son of Samuel Theobold and Mildred Burden.

- (Witness) Will: Samuel Theobold is mentioned in the will of George Theobold dated 26 March 1640 at Pett, Sussex, England; Unregistered Will (ESRO: PBT 1/5/282.)

- Marriage*: Samuel Theobold married Anne Latter, daughter of Edmund Latter and Agnes A'Downe, circa 1660 at England.1

- Occupation: Samuel Theobold was a clothier on 7 January 1661/62.

- Anecdote*: On 7 Jan 1661/62 Anne's son Thomas Barber leases the cottage in Rotherfield Town and the Drapers land from Ann and her third husband, Samuel Theobold, who were occupying it: "7 Jan 1661/62 Lease by Samuel Theobold of Tonbridge, Kent, clothier and Ann his wife, to Thomas Barber alias Nine, of Frant, Sussex, then servant to Thomas Weller, gent., of a messuage or tenement, outhouse, barn and stall and a small piece of land lying near the said barn, together with all gardens, closes, backside, etc. in Rotherfield Town. Also, 4 pieces of land and wood containing 22 acres, called Drapyers in Rotherfield; all which premises the said Samuel held by right of An his wife made to her by jointure and lease from Thomas Barber alias Nine, her former husband, father of the above named Thomas. Term, the life of the said Ann Theobold party to the deed and mother of the said Thomas: rent yearly 11 pounds/5s. Signature of Samuel Theobold, and mark of Ann Theobold & seals. Witnesses: William Jeffrey, Ann Barber (mk)".

- Anecdote*: It appears that Samuel and Anne lived in Tonbridge for the remainder of their life. The lease of 1661/62 states that Samuel Theobold is “of Tonbridge”, and there is another document dated 24 January 1670/71 in which Samuel Theobald, "of Tonbridge, yeoman", releases his step-daughter Anne Barber, spinster, from any obligation to him. This is clearly indicating a separation of affairs between Samuel and Anne Barber, but we do not know the circumstances behind it (was Anne about to be married?). The fact that this document ended up with Mary Barber's papers (wife of Anne's brother Thomas) indicates that the unmarried Anne Barber was still in touch with her brother (who was also unmarried at this time) and that perhaps he was assisting her in this matter. The document is transcribed below:

Knowe all men by these presents that I Samuell Theobald of Tonbridge in the county of Kent yeoman for good causes and considerations me hereunto moveing Have remised released and for ever quiteclaymed and by these presents doe fully cleerly and absolutely for and from me mine executors and adm[ini]strators remise releas and for ever quiteclaime unto Anne Barbar of Tonbridge aforsaid Spinster her heires executors and adm[ini]strators all and all manner of accons causes of accons sutes Controversies bonds obligations bills debts duties recconings accompts defamations wrongs assaults trepasses and demands whatsoever which I the said Samuell Theobald mine Executors adm[ini]strators or assignes have had may might could or ought to have of from or against the said Anne Barbar her heires executors or adm[ini]strators for any cause question matter or thing whatsoever from the beginning of the world until the day of the date of these presents In witnes whereof I the said Samuell Theobald have to this my present writing sett my hand and seale the fower and Twenteth day of January In the Two and Twenteth yeare of the Reigne of our sovereigne Lord Charles the second by the grace of God King of England Scotland France & Ireland defender of the faith &c Anno d[omi]ni 1670

Sealed and delivered in the

p[resen]nce of Geo. Hooper: &

Richard Polhill

Samuel Theobald.

(Transcribed by Gillian Rickard for Geoffrey Barber, April 2014.)2,1 - Occupation*: Samuel Theobold was a yeoman in 1670.

- Anecdote*: There is a document dated 24 January 1670/71 in which Samuel Theobald, "of Tonbridge, yeoman", releases his step-daughter Anne Barber, spinster, from any obligation to him. This is clearly indicating a separation of affairs between Samuel and Anne Barber, but we do not know the circumstances behind it (was Anne about to be married?). The fact that this document ended up with Mary Barber's papers (wife of Anne's brother Thomas) indicates that the unmarried Anne Barber was still in touch with her brother (who was also unmarried at this time) and that perhaps he was assisting her in this matter. The document is transcribed below:

Knowe all men by these presents that I Samuell Theobald of Tonbridge in the county of Kent yeoman for good causes and considerations me hereunto moveing Have remised released and for ever quiteclaymed and by these presents doe fully cleerly and absolutely for and from me mine executors and adm[ini]strators remise releas and for ever quiteclaime unto Anne Barbar of Tonbridge aforsaid Spinster her heires executors and adm[ini]strators all and all manner of accons causes of accons sutes Controversies bonds obligations bills debts duties recconings accompts defamations wrongs assaults trepasses and demands whatsoever which I the said Samuell Theobald mine Executors adm[ini]strators or assignes have had may might could or ought to have of from or against the said Anne Barbar her heires executors or adm[ini]strators for any cause question matter or thing whatsoever from the beginning of the world until the day of the date of these presents In witnes whereof I the said Samuell Theobald have to this my present writing sett my hand and seale the fower and Twenteth day of January In the Two and Twenteth yeare of the Reigne of our sovereigne Lord Charles the second by the grace of God King of England Scotland France & Ireland defender of the faith &c Anno d[omi]ni 1670

Sealed and delivered in the

p[resen]nce of Geo. Hooper: &

Richard Polhill

Samuel Theobald.

(Transcribed by Gillian Rickard for Geoffrey Barber, April 2014.)2 - Marriage*: Samuel Theobold married Martha Cheesman on 23 November 1676 at Tonbridge, Kent, England, (KHLC: P371/1/A/3). Note that this marriage may be for a son of Samuel Theobald as he may have had children from an earlier marriage that has not been found.

- Death*: Samuel Theobold died in 1694 at Tonbridge, Kent, England.

- Burial*: Samuel Theobold was buried on 27 June 1694 at Tonbridge, Kent, England, "Senr" (KHLC: P371/1/A/4.)

Family 1:

Anne Latter b. 11 Dec 1608, d. c 1675

- Marriage*: Samuel Theobold married Anne Latter, daughter of Edmund Latter and Agnes A'Downe, circa 1660 at England.1

Family 2:

Martha Cheesman

- Marriage*: Samuel Theobold married Martha Cheesman on 23 November 1676 at Tonbridge, Kent, England, (KHLC: P371/1/A/3). Note that this marriage may be for a son of Samuel Theobald as he may have had children from an earlier marriage that has not been found.

Children:

Edward Theobold b. 5 Sep 1677

John Theobold b. 11 Feb 1678/79

Susanna Theobold b. 18 Jun 1682

Samuel Theobold b. 17 Aug 1684

John Theobold b. 11 Feb 1678/79

Susanna Theobold b. 18 Jun 1682

Samuel Theobold b. 17 Aug 1684

Drapers Property at Rotherfield .

Last Edited: 10 Feb 2023

- Anecdote*: THE DRAPERS PROPERTY AT ROTHERFIELD

The property known as Drapers (or Drapyers) is located in the High Cross area of Rotherfield adjacent to another property called Grubreed. - Anecdote: “Drapers fronts the Mayfield Rd between Grubreed Cottages and Lew farm”.1

- Anecdote: In the 1597 survey of the manor of Rotherfield it was noted as 27 acres 0 roods and 10 perches in size, but was described as 22 acres in a lease dated 1662.

- Anecdote: The property is first mention in a 1296 list of tax payers (called a subsidy roll) as being owned by Alexander Draper and is still mentioned as "Drapers" in the 1911 census. It was in the Barber alias Nynne family for about 200 years from c1590 to 1787. Documents show that it was a valuable source of timber and was also used for crops, animals and fell mongering (variously mentioned in wills of 1627, 1683 and 1799).

The centre point of the property can be located using Google Earth at latitude 51° 2’ 21.76” North; longitude 0° 13’ 25.91” East. - Anecdote: History of Events.2

- Anecdote: 1296 Alexander Draper listed as owner in a subsidy roll (list of tax payers).

- Anecdote: 1509 Thomas Morley pays yearly rent of ijd (2 pence) for Drapers to Rotherfield Church.1

- Anecdote: 1597 The property is drawn on the 1597 survey of the manor of Rotherfield map and shows “Georg Barbar” as the freehold owner and indicates the size of the property as 27 acres 0 roods and 10 perches.3

- Anecdote: 1627 The property transfers to Thomas Barber alias Nynne on the death of his father George Nynne alias Barber.4

- Anecdote: 1649 On the death of Thomas Barber alias Nynne of Rotherfield the property is held by his wife Ann Barber as guardian for the young Thomas Barber alias Nynne (born 1640 Rotherfield). Ann Barber remarried Samuel Theobold of Tonbridge and they occupied the property (and a cottage in Rotherfield town).5

- Anecdote: 1662 On coming of age, Thomas Barber alias Nynne leases Drapers and the cottage in Rotherfield town to his mother Ann for life for the rent of £11/5s per year. Thomas is working in Frant at this time, and later moves to Tonbridge (Hildenborough) where he marries in 1672 and has a family.6

- Anecdote: 1683 Thomas Barber (alias Nynne) died and was buried 1 Nov 1683 at Tonbridge, Kent. His will was proved on 14 Dec 1683 stating " I will and giv unto mary my loving wif all my lands lying in Rearfel [Rotherfield] in the couty of sothsex known by the name of Dreapars or by any other name or names what so ever for term of har natarall life with libarty to sell the timbar now standing theron within the spas of thre years aftar my desis preserving the under wads [underwoods ?] and timbar that shall renew grow or incres theron derring har natarall life and aftar har deses for the yeus of my to sons Ricard Barbar and Thomas Barbar paying therout to Elizabeth Barbar my daftar the some of forty and fif poundes with in too years aftar my wifs deses".7,8

- Anecdote: 1684 His widow Mary was quick to act and in a document dated 29 January 1684, she leases the Drapers property to John Lockyer of Rotherfield for the sum of £6/10s per year for a period of 11 years.

- Anecdote: 1709 According to Pullein, by 1709 John Moone of Rotherfield "for some years had held ...... Drapers". He would have been the occupier as opposed to the proprietor or owner, so the land would have been leased at the time. Pullein incorrectly ascribes the ownership to Holman.9

- Anecdote: 1720 A record survives of Mary Barber paying the annual rental for Drapers to the manor of Rotherfield "Mary Barber of Tunbridge, widow for Drapers 3s/4d".10

- Anecdote: 1732 Mary Barber was buried at Tonbridge on 4 May 1732. While no will or transfer record has been found, Drapers likely passed to her eldest surviving son, Thomas Barber, who passed all his properties to his nephew Thomas Barber of Tonbridge (son of Richard, the eldest son of Mary) in his will of 1749.11,12

- Anecdote: 1754 Thomas Barber died prematurely in 1754 leaving the property with his widow, Elizabeth Barber of Tonbridge, and their only child Thomas, born in 1752.

- Anecdote: 1750-64 Land tax records show the property owned by "Mr. Barber" but leased to John Parsons. Elizabeth would have held the property for her only son Thomas.13

- Anecdote: 1765-87 Land tax records show the property was owned by "Mr. Barber" but leased to William Peerless.13,14

- Anecdote: 1788 William Peerless appears on the land tax records as the owner of the property. It is presumed that Elizabeth Barber or her son Thomas sold the property in 1787.13

- Anecdote: 1800 The will of William Peerless, a glover and fell monger, leaves Drapers to his son Henry Peerless with his younger son William Peerless having the right to occupy and make a living from the property as long as he remains in Rotherfield and continues in business as a glover and fell monger. William Peerless was buried at Rotherfield on 19 Oct 1800 with his occupation noted as currier, and his will proved on 7 Nov 1800. His son Henry Peerless married Mary Miles on 2 Aug 1798 at Rotherfield. The marriage licence states that Henry is a breeches maker of Speldhurst age 24+ and Mary is a spinster of Rotherfield, age 22+. Henry died in 1821, age 47 years, and was buried at Rotherfield on 5 Jan 1821.15,16

- Anecdote: 1831 The Rotherfield manorial court of 19 Sep 1831 is advised of the death of Henry Peerless in 1821 and that he held the freehold Drapers "by fealty, suit of court, heriot, relief and other services and the yearly rent of three shillings and four pence". The heriot was deemed to be nothing as Henry had no living animal but an accrued relief of three shillings and four pence was payable. However, no person was present in court so the bailiff was ordered to distrain for the same. This was a very late notification to the court. Henry Peerless left a will made 7 Dec 1820 in which all his real estate in Rotherfield was left to his two sons William and Henry Peerless as tenants in common subject to a number of conditions. The will was proved in London on 11 May 1821 (PCC: PROB 11/1643). The son William died in 1826 and his will was proved 30 Aug 1826, leaving his share to his brother Henry (PCC: PROB 11/1716).17

- Anecdote: 1833 In an indenture dated 16 Sep 1833, the property was mortgaged for £300 to Thomas Babington.

- Anecdote: 1841 An indenture dated 13 Oct 1841 conveyed the property "Drapers Farm" from Henry Peerless of Tunbridge Wells, Fellmonger, to Nicholas Stone of Mayfield, Gentleman, and John Baker of Heathfield, Gentleman, in settlement of the mortgage, then valued at £361 13s 4d, plus £80 paid to Henry Peerless. The conveyance was "subject to the estate of Mr. William Peerless". (ESRO: ACC 14058.)

- Anecdote: 1861 Census - a cottage at the location “Drapyers” next to Grubreed is occupied by agricultural labourer George Richeson with wife Ann and children George, Flora and William.18

- Anecdote: 1871 Census - a cottage at the location “Drapyers” next to Grubreed is occupied by William Haywood, a jobbing gardener, and his wife Betsy and daughter Eliza.19

- Anecdote: 1881 Census - no reference to “Drapyers”. The cottage at this location was now called “Spring Cottage”. The name of its’ neighbouring property “Grubreed”, however, was still being used.20

- Anecdote: 1911 Census - the household next to Grub Reed cottages is given the postal address of "Drapers, Rotherfield”, indicating that the name was still in use. The house was occupied by Alfred and Ada Crittall, and their two sons. Alfred was a general labourer. The name had not been forgotten. Is it still remembered today?21

- Anecdote: Image: Drapers in 2011 on Google Earth.

- Anecdote: Image: Drapers on the 1597 map of Rotherfield. Compare this to the 2011 Google Earth image.

Citations

- [S104] Catharine Pullein, "Rotherfield: The Story of Some Wealden Manors", Courier, First Edition (1928) "page 235."

- [S104] Catharine Pullein, "Rotherfield: The Story of Some Wealden Manors", Courier, First Edition (1928) "page 56."

- [S105] Survey (map) of land held of the Manor of Rotherfield, "described in the Year 1597 by Richard Allin of Roberstsbridge in Sussex, and new drawn on vellum and collored in the yeare 1664 by John Pattenden of Brenchley in Kent", of the manor of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, 1597 (ESRO: ACC 363/111r).

- [S120] Transcription of Thomas Nynne als Barber Admission, 24 Jul 1627. (ESRO SAS AB 397).

- [S103] Transcript of the Parish Register of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, (ESRO: PAR 465/1/1/1).

- [S117] Transcription of Theobold/Barber alias Nine Lease, 7 Jan 1661/2. (ESRO SAS FA 781).

- [S3] Will of Thomas Barber of Tonbridge, Kent, England, made 28 Oct 1683, proved in the Archdeaconry of Rochester, 14 Dec 1683. (KHLC: DRa/PW4).

- [S534] Various Papers of the manor of Datchurst alias Hilden, Kent, England, 1608-1808 (KHLC: TU1/M2/1).

- [S104] Catharine Pullein, "Rotherfield: The Story of Some Wealden Manors", Courier, First Edition (1928) "page 156."

- [S106] Rentals of the manor of Rotherfield, 22 Apr 1720 (ESRO: ACC2953/130).

- [S133] Transcript of the Parish Register of Tonbridge, Kent, England, 1547-1730 (KHLC: TR 2451/20).

- [S341] Will of Thomas Barber of Tonbridge, Kent, England, made 16 May 1749, proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 16 Jun 1749. (TNA: PROB 11/770/346).

- [S124] Land tax of the manor of Rotherfield, Sussex, 1750-1779 (ESRO: XA31/34).

- [S729] Roger Davey, "East Sussex Land Tax 1785", Sussex Record Society, First Edition (1991) "p. 178."

- [S129] Will of William Peerless of Rotherfield, Sussex, England, made 9 Feb 1799, proved in the Archdeaconry court of Lewes, 7 Nov 1800. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/68/507).

- [S24] Index to Marriages, 1538-1837, Compact Disc SFHGCD003, compiled by Sussex Family History Group, 2008.

- [S843] Court Rolls of the manor of Rotherfield, 1815-1842 (ESRO: ABE 74O1).

- [S68] 1861 Census for England, "RG09/574/7/8."

- [S69] 1871 Census for England, "RG10/1050/10/12."

- [S70] 1881 Census for England, "RG11/1050/5/4."

- [S73] 1911 Census for England "RG14PN4935 RG78PN214 RD74 SD1 ED8 SN62."

Manorial Records .

Last Edited: 27 Jul 2021

- Anecdote: The following is a brief introduction to manorial records. It is recommended that the interested reader follow this up by reading the author's book "Manorial Records for Family Historians" published by Unlock the Past (see Publications page).

- Anecdote*: Understanding Manorial Customs and Courts

© Geoffrey Barber 2015, 2018.

During the 16th and 17th Centuries the Barber alias Nynnes lived under the rules and customs of the manor of Rotherfield. As tenants of the manor they were required to attend and participate in the manorial courts and were collectively responsibility for maintaining law and order as there was no local police force. The manorial records show that they served in various roles such as headborough, constable and jury members. As part of a small village community they also served their parish church as churchwardens and in one case, a church sexton. This community service was in addition to the pursuit of their normal occupations. We know about this because of the survival of the manorial court records and church records.

Genealogists are usually well aware of the church records (parish registers, churchwarden's accounts books, overseers of the poor disbursements and accounts, etc) but fewer have an understanding of manorial records and how the manor operated. As much of the material for my research has come from manorial records, I feel that it is important to provide the reader with a basic understanding of the manor and manorial courts before proceeding further. This will greatly assist the reader to understand the information presented on this site.

Feudalism

The system of manorial land tenure, broadly termed feudalism, was conceived in Western Europe and exported to areas affected by Norman expansion during the Middle Ages and in particular to England after the Norman conquest where it was well established by the time of the Domesday Book (1086). It is important to realise that it had many local variations, and evolved considerably between 1100 and the 1500-1800 period considered in this book. In particular, the time of the Black Death (1348) caused severe labour shortages and resulted in many improvements in conditions for manorial tenants, which were quite severe in earlier times. The manorial system is considered to have peaked in the 13th century and entered a period of slow decline thereafter. It was not completely extinguished until 1922.

In England, the dukes, earls and barons who received their lands directly from the king were known as tenants-in-chief. They gave out portions of their lands to knights, esquires and gentlemen who were therefore lords of manors held indirectly of the king. The lord of the manor had legal authority and was supported economically from his own direct landholding in the manor and from the obligatory contributions of the people under his jurisdiction. These obligations could be met by providing labour, payment in kind or with money. As the manorial system declined these obligations became increasingly met by purely financial payments.

The rules and customs under which the manor operated were documented in a "Custumal of the Manor" and the custumal for the manor of Rotherfield survives and is translated in Catherine Pullein's book "Rotherfield: The Story of Some Wealden Manors" (Chap. VI). It documents the customs under which the tenants held land from the lord of the manor, the services they owed him and the monies they had to pay if those services were not performed. It included a local code of laws regarding personal behaviour and a summary of oral sworn tradition and written legal arrangements between the landlord and his tenants. Custumals were compiled for a practical purpose: to guide and educate successive generations of officials tasked with keeping law and order within the manor. They were modified from time to time to meet the changing interests and needs of their communities.

What is a Manor?

A manor was an area of land held by feudal tenure, generally from the Crown, so that the lord of the manor was a tenant of the Crown with many obligations - financial, military, law and order, religious, etc. It was very much a social and economic unit, with some of the land held by the lord for his own use and the remainder tenanted by local people or used as common land or waste.

Manorial courts regulated the administration of the manor by enforcing local customs and agricultural practices, settling minor disputes and debts and transferring property rights. Much of the business of the court required fees to be paid and was an important source of revenue for the lord. All tenants of the manor were meant to attend the courts and could be fined for not doing so. From the sixteenth century onwards a property was only considered a manor if its owner held a court for the tenants.

In the early days of the manorial system there were two types of tenants of manorial land:

1. Villeins (unfree tenants) - who occupied their lands on condition of rendering services to the lord such as farming his land. Villeins were effectively chattels of the lord and subject to severe restrictions on their personal freedom. They needed permission to move away from the manor, to allow their daughters to marry, and to educate their sons. These personal restrictions eventually disappeared following the outbreak of the plague in the 14th century which created severe labour shortages and left all tenants in a much stronger bargaining position.

Villein land tenure eventually evolved into what was called copyhold tenure and by the 16th century the obligation for service had largely been commuted to monetary payments so that copyhold tenants functioned virtually as free tenants after having paid their rent. This commutation of labour services to monetary payments is a major theme in the evolution and decline of the manorial system. It is worth noting that these monetary payments were often fixed and their value to the lord diminished over time.

2. Freemen (free tenants) - who occupied their lands for a money rent paid to the lord in lieu of providing services and as a result had considerable independence. This type of tenure was called freehold.

Both types of tenants had an obligation to attend the manorial courts and to pay homage to the lord. The lord of the manor could hold separate courts for customary tenants (copyholders) and freeholders but it was usually more convenient to deal with both in a single court session. This was the case in the surviving Rotherfield manorial records as most freeholders held copyhold property as well.

Social division however came to be based more on wealth and through holding office in the community rather than these categories of freemen and villeins. There was not necessarily a correlation between a person's wealth and the type of land tenure - an unfree tenant might hold more land that his free neighbour and thus be wealthier.

In the administration of the manor the Steward was the chief official (often a lawyer who may serve more than one manor) who held the courts at which lower, appointed officials were bound to attend in person or by deputy.

Some of the other official positions were the bailiff, reeve, hayward, constable, headborough, warrener (gamekeeper), parker (caretaker of a park) and woodward or wood reeve (forest keeper).

Land Tenure

The different ways in which land was held and inherited is the very essence of feudal society and an understanding of this is crucial to interpreting manorial records:

Demesne land was land held by the lord of the manor for his own benefit (demesne is pronounce de-main and is a variant of the word domaine but with a more specific meaning). Other landholders (originally the villeins or unfree tenants but later called copyholders) had significant obligations to farm and maintain this land for the lord's benefit, although this declined over time and was eventually replaced by a fixed rent (called a quit rent) and the lord's land came to be cultivated by paid labourers. Eventually many of the demesne lands were leased out either on a perpetual (i.e. hereditary) or a temporary renewable basis.

Copyhold or customary tenure - originally called villein tenure where the land was held in exchange for payment and services provided to the lord of the manor, although the land was still technically owned by the lord. Villein tenants came to be called customary holders/tenants because they held the land at the will of the lord of the manor according to the custom of the manor and all conveyances of this land, including descent to an heir, had to pass through the lord's manorial courts. A more secure form of tenure called copyhold developed from this and was fully established by the start of the 16th century. Unlike the earlier form of villein tenure, the obligations to the lord extended only to the payment of an annual cash rent (called a quit rent), suit (attendance) at the manorial court, an entry fine (a fee payable when a new person was admitted to the property), and a heriot (tax) on death of the tenant. The tenant received a written copy of the court roll entry recording their admission to the property hence the term copyhold tenure and although the land was still held "at the will of the lord according to the custom of the manor" it became largely independent of him. An example of a copyhold "title" is shown here. - Anecdote: One of the important tasks of the manorial courts was to record the death of copyhold tenants in the court books, the name of their heir and the name and description of their lands. The land was first "surrendered" back to the lord and the heir then "admitted" to the land. If no heirs existed, the property would revert to the lord's holdings. Copyhold properties could also be sold and would undergo the same procedure of surrender and admission. An example of a manorial court document recording this process is shown later in the chapter in Fig. 4 and concerns a property held by Thomas Nynne alias Barbour being transferred to Edmund Latter, presumably the result of a sale.

One of the customs of the manor was that when a customary/copyhold tenant died the lord shall have his best animal in the name of a heriot (a feudal due), and this was generally required to be paid before the heir was admitted to the property. We see an example of this when Thomas Nynne alias Barber was "admitted" to a property on 24 July 1627 after the burial of his father George on 11 April 1627 and that the heriot was "1 Ox color red branded".

The privilege of the widow to retain tenure of her late husband's copyhold land during her lifetime was called "free bench" and was in fact more generous than that which applied for freehold land where the widow was entitled to hold only a third of the property which was called her "dower". It was called free bench because she became a tenant of the manor and therefore one of the people who sat on the bench occupied by the peers of the manorial court.

The manorial court was generally quite protective of the rights of young children as heirs to a copyhold property when the father died. The widow could not marry without permission or be unchaste otherwise the lord could forfeit her property. Generally a second husband was only allowed to enter his wife's property on sufferance, for the term of her life, and often only during the minority of her children. While it was possible for a wife to surrender her right and seisin (meaning possession) of a property to a new husband, it could only be with the lord's permission and was quite rare.

On the death of a widow, a property usually went wholly to one of the children (the heir). Division of property was generally not a feature of the manorial system. In early times the identity of the heir was determined by the custom of the manor which for most of England was primogeniture (i.e. the eldest son) although the Statute of Wills enacted in 1540 allowed landholders to determine who would inherit by permitting bequest by will. Most wills, however, usually left the landholdings to the eldest son and gave financial compensation to the other children. Where significant property was involved, the heir would likely have had additional financial responsibilities to the wider family such as looking after unmarried sisters and older family members. Sometimes these additional responsibilities were made explicit in the will.

Copyhold tenure was abolished by the Law of Property Act of 1922 (enacted 1926), when all copyhold land became freehold, effectively ending the manorial court system. However, the process of converting copyhold to freehold (called enfranchisement) had begun much earlier and became common in the late 19th century.

Freehold land was owned absolutely by the owner who was free to sell it and pass it by will, and so its descent was not governed (or recorded) by the manor. No services were due to the lord except the payment of a fixed rent, liability to "suit" (attend) at the lord's court and to be subject to the lord's jurisdiction. The freeholder was also subject to paying an entry fee (called a relief which might be one year's rent) when the property was purchased or inherited. Because custom played a big part in determining these obligations they could be quite different between manors. For example we find in Kent that freehold tenure could also entail the payment of a heriot on death (as for copyhold).

Freehold tenure was anciently thought the only form of feudal land tenure worthy to be held by a free man. However, in the 16th century in Rotherfield the local people (at all levels) often held lands under both types of tenure. This was certainly the case for the Barbers when they lived in Rotherfield and also later in Hildenborough. The 22 acre property called Drapers at High Cross, Rotherfield was held freehold and as a result it is rarely mentioned in manorial records other than in the accounts where rents are recorded. On the other hand, their house (called Bonnetts) in the Rotherfield village was held copyhold and has an extensive history of surrenders and admissions in the manorial court records as it passed from one generation to another.

On the death of her husband, a widow was entitled to hold one third of her husband's freehold property and this right was called dower. However, it was common for a wife to make an arrangement before marriage whereby she exchanged her right of dower for jointure, which was a specified interest in her husband's property after his death - a particular share, a life interest or an annuity. If she brought property to the marriage then her share in jointure would be expected to be greater than that which she would get under the dower entitlement. Dower applied strictly to freehold property. Jointure however could apply to both freehold and copyhold as it was possible for a copyhold tenant to be given the power to appoint a jointure for his wife. Freehold land descended by Common Law to a man's heir (who was usually the eldest son) so in the case where there was a widow entitled to her dower, the heir would inherit the rest of the property provided that he had come of age. If he was underage, a third party was appointed to hold the land until he reached his majority.

We see an example of dower when Thomas Barber died intestate in 1756 in Tonbridge, Kent. His widow Elizabeth received her right of dower and twenty years later there is a legal agreement (an "Indenture" dated 29 January 1776) where she releases her dower to her 23 year old son Thomas. This agreement is not a manorial document as the transaction pertained to freehold land. It is simply an agreement drawn up by a lawyer and signed by the parties involved (in this case only Elizabeth's signature was required). - Anecdote: This section has discussed in some detail the different types of land tenure and some of the issues regarding inheritance as they are often the main subject in many of the surviving manorial documents. At this point it would be instructive to look at the 1597 map of the survey of the manor of Rotherfield where these different types of land tenure are clearly marked. Freehold land is labelled "free" (for example, Georg Barbar's [sic] property), and the demesne land is labelled "demains". Anything not labelled free or demains would generally be held by copyhold tenure.

- Anecdote:

Manorial Courts

Manorial courts regulated the administration of the manor by enforcing local customs and agricultural practices, settling minor disputes and debts and transferring property rights, notably copyhold tenure. All tenants of the manor were meant to attend and could be fined for not doing so. The written records of the proceedings of these courts (court rolls) form the largest part of what we call manorial records.

In addition to manorial courts there was also the common law courts which were administered nationwide under the authority of the monarch. Over time, people were able to resort to the common law courts to resolve their differences over tenure rather than the manorial court. So when studying manorial court rolls we must realise that we are seeing only those matters which came under the jurisdiction of the manorial court and is therefore not a full picture of "life on the manor".

The two main types of manorial courts held are described below:

The Leet Court had certain rights of criminal jurisdiction and of appointing some local officials. A system called "Frankpledge" maintained law and order within the manor. It was a system of mutual responsibility within a group of originally about ten households - i.e. they were held corporately responsible for the behaviour of each member and for their appearance at court. The Leet Court was held to examine each group ("inspect" the working of frankpledge) and was also known by its older name, the "View of Frankpledge" . There were three such groups (also called tithings) on the manor of Rotherfield in the 16th century: Southborough, Northborough and Frant.

At this court the tenants of the manor (called the homage) assembled and swore fealty. A jury, either formed from the homage or synonymous with the homage, decided on the fines payable for offenses, appointed the officers of the manor such as constables and headboroughs, and heard the cases against miscreant tenants. Each group (or frankpledge or tithing) reported to the court via their elected headman or headborough. The court had the power to deal with offences such as common nuisances, affrays, the condition of highways and ditches, and the maintenance of the assize of bread and ale (from 1267 the price of bread and ale was fixed based on prevailing prices of corn and malt). We find in 1631, 1632 and 1634 that Thomas Barber was a member of a three person jury at such a court.

The Leet Court was the lowest level of criminal court in England and more serious offences would be dealt with by the Hundred Court. Reforms to the justice system in Tudor times meant that the role of this court effectively disappeared in the 17th century.

The Court Baron was concerned with the lord's "incidences", especially what was due to him from movement of tenants. This court enforced payment of all fines (fees) and services due to the lord. Surrender, admission, death, marriage - all entitled the lord to a monetary payment. These fines were recorded, along with details of the incident giving rise to them, in the court roll (book). This court also appointed some local officials including the reeve, bailiff and the hayward.

From the seventeenth century we often see instances of a private court baron being held. This was an ad hoc meeting of the court with only a few suitors present and was probably held to address an urgent piece of business.

An example of a page from a Court Baron roll from the manor of Rotherfield dated 6 December 1677 is shown here. - Anecdote: Note that the court rolls were recorded in Latin up until 1733 (with the exception of the period of the Commonwealth) even though the proceedings were conducted in English.

The document starts by identifying the lord of the manor and stating that the steward Thomas Hooper is holding the court. It then proceeds to list the essoins (those excused for non-appearance at court), the homage (the tenants attending the court) and then lists the business of the court.

The first item on this particular document records the surrender of the properties called Bonnetts and Bathelands by Thomas Nynne alias Barbour and the admittance of Edmund Latter to the same property. The reason for the transfer is not given (it was probably sold to Edmund Latter) as the manorial record is primarily concerned with recording the change of ownership and the fee of £3/13s/4d due to the lord of the manor. It reads:

Rotherfield. Court Baron of William Dyke, Esquire, and Ralph Snowden, held in the same place for the tenants of the aforesaid manor on the sixth day of December in the 29th year of the reign of our Lord Charles the Second, by the grace of God, now King of England etc, and in the year of our Lord 1677, by Thomas Hoop [or Hooper], gentleman, steward.

Essoins: None

Homage: Nicholas Hosmer, Abraham Alchorne, Thomas Hosmer (sworn)

To this Court came Thomas Nynne alias Barbour and surrendered into the hands of the Lords, by the acceptance of their aforesaid steward, one messuage or tenement, one garden and one barn, called Bonnetts, and a certain way leading from the messuage to the aforesaid barn, and also one other garden containing one rood of land called Bathelands lying near the aforesaid barn, and one piece of meadow containing half an acre, and one wooden building, in English a lodge or hovel, and one garden previously Adam Fermor's, situated and lying in Retherfeild, held by rent of [blank], heriot, relief and other services, to the use of Edmund Latter and his heirs, according to the custom of the aforesaid manor. And thereupon to this court came the aforesaid Edmund and sought that he be admitted to the messuage, tenement, barn, garden, lands and premises aforesaid, with the appurtenances, to whom the lords, through their aforesaid steward, granted seisin thereof by rod, to have and to hold to the same Edmund and his heirs, at the will of the lords, according to the custom of the aforesaid manor, by the rent and services formerly due in respect thereof and by right accustomed. And he gave to the lords, as fine and heriot, a composition, £3 13s 4d. And he is admitted as tenant thereof. And he has seisin by rod. And he makes fealty to the lords.

(Transcribed by Gillian Rickard for Geoffrey Barber 2011)

Proceedings of all the courts may be recorded on the same manorial court roll and often the proceedings of the Court Leet and the Court Baron were not kept distinct. It is important to note that not all matters considered by the manorial courts were recorded in the court roll which was concerned mainly with recording items affecting the lord's financial interests. For example, the agricultural routine of the manor was regulated by the court but rarely documented.

There were other courts convened from time to time such as a court of survey undertaken to compile a formal survey of the manor and a court of recognition undertaken when a new manorial lord had taken over and whose purpose was to record all the tenants and their holdings and to gain acknowledgement of the rents and services they owed (which could include the steward reciting the customs of the manor).

The manorial courts provided a process for local government and law and order within the community and it is the surviving court rolls for the manor of Rotherfield in Sussex and also the manor of Datchurst in Tonbridge, Kent that have provided significant information on the Barber family and their properties.

Further Reading

1. Geoffrey Barber, "Manorial Records for Family Historians", 2nd Edition, Unlock the Past, 2018. [See Publications section]

2. Mary Ellis, "Using Manorial Records", PRO Readers' Guide no. 6, PRO Publications in association with the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, revised edition, London, 1997.

3. P.D.A. Harvey, "Manorial Records", British Records Association, revised edition, Loughborough, 1999.

4. John Richardson, "The Local Historian's Encyclopedia", Third Edition. Historical Publications Ltd., 2003.

5. N. J. Hone, "The Manor and Manorial Records", Methuen, London, 1906.

6. H. S. Bennett, "Life on the English Manor 1150-1400", Cambridge University Press, 1937.

7. Denis Stuart, "Manorial Records: an introduction to their transcription and translation", Phillimore, 1992.

8. Mark Bailey, "The English Manor c.1200-c.1500: selected sources", Manchester University Press, 2002. - Anecdote:

© Geoffrey Barber 2015, 2018.

Introduction .

Last Edited: 4 Apr 2022

- Anecdote*: I first met my English grandmother in 1985 when she was 87 years old. It was my first time in England, courtesy of a business trip to attend a mining conference in Birmingham. On this first visit I had an epiphany. I had arrived in Brighton to stay with my uncle only to find that he was out, so an elderly neighbour kindly invited me in for a cup of tea while I waited for his return. This lady was exactly like my mother in her speech and her mannerisms and in a moment of sudden awareness I felt the door open to a deeper understanding of my mother. I understood that this place and these people had made her and consequently that it had largely made me even though I was raised in Australia. This helped to trigger a greater search for understanding through family history.

The search for the Barber family history began in my parent’s hometown of Brighton in East Sussex. My mother had a good memory for family matters so I made an excellent start getting birth, marriage and death certificates and working back through the census returns. In the 1851 census I discovered that our earliest Barber in Brighton was born in Tonbridge in Kent and, with the help of genealogist Gillian Rickard,started to build an interesting picture of the Barbers who lived there which included three generations of malsters (makers of malt) and a long history of property ownership. A marriage licence dated 1672 between Thomas Barber alias Nin and Mary Rootes both of Tonbridge revealed the first usage of “alias Nin” in the surname, and the mention of a property called Drapers in Thomas’s will of 1683 was the means by which earlier generations were traced back to Rotherfield in Sussex. The existence of a surprising amount of manorial records, wills, church records and published research for Rotherfield enabled the line to extend back to 1530, nearly five hundred years of family history.

There are three localities where the families lived: Rotherfield c1530-c1670, Tonbridge c1670–c1800, and finally Brighton c1800–1950. While we can never know what these people were like we can try to get an understanding of their lives based on their family events, their occupations, the property they owned and the positions they held in the community. Sometimes we can feel quite close to them, such as when we read of the “waistcoat that is at the tailor’s a-making” in Elizabeth Barber’s will of 1637.

Their family history begins at the very beginnings of church records (the recording of baptisms, marriages and burials commenced in 1538) and even back a little further through manorial records. I have been very fortunate with this research, much of which has been possible because of research and transcriptions done by others in the past. I have been told that it is a rare achievement indeed to have gone back so far in such detail.

It includes about 200 years of ownership of a property in Rotherfield called Drapers which is clearly shown on a 1597 map of the lands of the manor of Rotherfield as being held by Georg Barbar. A list of tax payers in the 1296 Sussex subsidy roll for Rotherfield includes an Alexander Draper and Pullein links him to the property suggesting that he was probably one of the earliest owners. Other Rotherfield properties which were owned by the Barber family include a cottage in the village called “Bonnetts” and a small area of associated land called “Bachelands” which may have connections to John Bache, rector of Rotherfield St Denys 1406-1430. Bonnetts and Bachelands were owned by the Barbers from 1530 and sold in 1677, a few years after the family had moved to Hildenborough in Kent (near Tonbridge), although the more valuable Drapers property was kept until 1787. The income from the Drapers property was probably very important to the prosperity of many generations of Barbers and although they were not wealthy it allowed them to remain land owners and operate their own farms and businesses. They were able to purchase or lease other properties in the Tonbridge area including a house in Hildenborough purchased in 1691, Finches (4 acres) in Tonbridge purchased in 1743, and Tonbridge town site land and shops, some of which was still owned at the time of Mary Barber's death in 1841.

By the late 1700s the Barbers appear to have been in a very comfortable financial position, although it appears that a business venture in Ightham (near Tonbridge and pronounced “Item”!) may have caused the loss of some of their properties. In the early 1800s the family dispersed from Tonbridge with the eldest son Thomas Barber moving to Brighton in Sussex. The move to a larger city saw their occupations change and three generations of cabinet makers/carpenters followed resulting in the families moving from the propertied positions they had in Tonbridge to a more working class existence based on employment with less opportunity for financial improvement. In the case of my own family, this eventually led to migration to Australia seeking better opportunities and higher wages.

In terms of social status, the Barbers never made it into the gentry but sat just below at the yeoman/husbandman level (gentry were entitled to call themselves “Gentleman” or “Mr. and/or Mrs.”, short for Master and Mistress, and it was this small minority of gentry and those above them that controlled most of the wealth and decision making in England - the title “Mrs.” indicated social status, not marital status, and could be used by a married woman, a widow or a maiden). They were yeoman/husbandman from at least c1500 to c1800; a time when the Industrial Revolution in England (c1780-1840) was starting to affect everyone’s livelihoods. In economic history, the Industrial Revolution is regarded as the most significant event since the domestication of plants and animals, starting with mechanized spinning in the 1780s with high rates of growth in steam power and iron production occurring after 1800. It affected almost every aspect of life and was responsible for ending a system where most people lived and worked within a family environment, replacing it with the more productive, but socially alienating, industrial factory system. Laslett’s book “The World We Have Lost” defines gentry as those having sufficient wealth to not have to work with their hands out of necessity. The yeoman farmer (who owned his land) and the husbandman (a farmer who rented his land) were immediately below gentry, followed by craftspeople and tradesmen, then labourers and finally cottagers and paupers. People at these lower levels still held important positions in the community, such as churchwarden, parish clerk, constable, overseer of the poor, etc., but their public life was usually restricted to their local village or town. The records show that the Barbers played an active role in the community at this level.

Having spent many years on this project I feel it would be remiss of me not to make some personal observations about the family history. While recognising that we have limited knowledge of the actual people involved and the challenges they faced, I feel that there is some wisdom to be gained. Here are my observations:

1. The period 1500-1785 appears to be a time of increasing prosperity for the family despite four consecutive generations where the husband died early leaving a widow with a young family. The involvement of extended family members and trusted business connections such as the Wellers in Rotherfield and Tonbridge, and the Polhill and Children families in Tonbridge, is seen again and again in the records. In most cases properties were held for long periods of time and purchased from, leased or sold to other family members. It appears they looked after each other’s interests. This may have been out of necessity – you needed to deal with people you could trust – but it also appears to have been effective. Extended family and connections were important.

2. Marriage was often a practical arrangement, sometimes postponed until an inheritance was received or occurring after a widowed mother had died, suggesting perhaps that there was a need for a woman to manage the house and also that financial arrangements needed to be in place in order to attract a suitable bride. We must remember that these were times when love was not necessarily the main factor in a marriage and also that there was a lot of work in running a self-supporting household that would have farmed, grown, stored and cooked its own food, baked bread, brewed beer, etc. Much of this would have been the responsibility of the women in the household and an unmarried son inheriting a house or cottage would be in need of a partner. The marriage in 1639 of Thomas Barber (age 54) to the widow Ann Heath (age 30 years), just four months after the death of his mother, appears to fall into this category especially when one considers that there is evidence of a marriage settlement (property rights) being given to Ann at the time of their marriage. The marriage of Thomas Barber to Elizabeth Waite in 1749, just five months after he inherited from his unmarried uncle, is probably another example. These are indications that obligations to family and having the money and property to establish a separate household were important factors in the decision to marry. Family approval was often essential where property was involved and usually required finding a partner of similar social status. However, marriages were by consent and generally not “arranged” (except perhaps in the nobility) and the importance of companionship in marriage was valued. The wills left by the husbands do reflect genuine affection and concern for their wives and indicate to me their importance and status in the family especially when we also consider that as widows they showed they were more than capable as heads of their families.

3. I am often drawn to the example of the unmarried uncle, Thomas Barber (1675-1749), a malster whose hard work built up a prosperous business in Tonbridge making malt from barley and who successfully involved his nephew Thomas Barber whose father had died when he was only 9 years old. He eventually passed the business and his accumulated properties to the younger Thomas while also looking after other members of his extended family, especially his sister Elizabeth and her family. He appears to have played an important role as a family elder given the early death of his brother Richard who left his wife Margaret with five young children under the age of 9 years. His nephew Thomas and his other nephew Richard did not marry until after the uncle died. I think this is another example of where hard work and some sacrifice were required in serving the best interests of the family.

4. Ownership of property over long periods of time probably created much of the wealth, and more importantly, provided an income to the family in hard times. As well as providing income to the widowed families, it also allowed the family to pay an annuity to older parents, equivalent to our modern old age pension. There are two documented examples of this in the Barber family – one in 1662 and another in 1776 – indicating that it may have been a common practice in families that could afford to do so. Having property was important for keeping their families safe and secure and I feel there are lessons here in the importance of financial independence and in the custodianship of assets across more than one generation.

5. The decline in Barber family wealth in the 1800’s and 1900’s is obvious and coincides with the move to the cities and the industrialisation of England in general. With assistance from his family, Thomas Barber established a business in cabinetmaking/undertaking in Brighton with later generations seeking employment in cabinet making and carpentry and ultimately becoming unskilled. Working for others is generally not the path to wealth, especially in the trades. The move to Australia in 1950 provided access to better wages and gave the ability to save money for home ownership, something which was no longer possible for the family in England. Interestingly, the wider access to higher education in the 20th century has allowed children to seek more professional (and higher paid) levels of employment and our current generations are benefitting from this. Where this leads is for future generations to decide.

There are now three generations of us in Perth, Western Australia, where we are content and well settled. I hope this family history will give all descendants a deeper sense of place and an understanding of who we are, always remembering that it is our free will which gives us the ability to make our own history and set new directions as my parents did in 1950.

I must acknowledge the wonderful work done by Catharine Pullein in her book “Rotherfield: The Story of Some Wealden Manors”, published in 1928. This book is a treasure to those who have an interest in the history of the parish of Rotherfield. I would, however, like to point out two small errors in the book relating to the Barber alias Nynne family.1 - Anecdote: 1. Firstly, Chapter XIX, page 223 in the list of churchwardens - a John Wynde is listed for 1532. This should be John Nynde (who is actually the same person as the John Barber listed for 1531).

2. Secondly, Chapter XIII, page 156, fourth paragraph, states that in 1690/91, according to the Rates Book, John Moone "for some years he had held the Holmans' twenty-two acres called Drapers". He may have held it as a tenant, but the property was owned by Mary Barber in Tonbridge at that time (see Appendix I).

Last year I obtained a copy of Catherine Pullein's handwritten transcriptions of the churchwarden's accounts book and five volumes of manorial court rolls transcribed from Latin. The existence of these documents was previously unknown and they came to light when they were handed to Alan Yates, Archivist for the Rotherfield St Denys Church, by the grandson of a deceased former churchwarden who had kept them in a box in her flat. They represent a wonderful find and have provided new information regarding the Barber alias Nynnes in Rotherfield. They are an example of the enormous amount of work done by Pullein for which I am very grateful. I was with Alan when he handed these over to the East Sussex Record Office at The Keep on 9 April 2014.

Family history research never finishes, but at some point one needs to decide to publish in order to make it available to a wider audience. Long term preservation of the information is also a consideration, and a hardcopy book still offers greater security over digital copies which can be so easily deleted and lost. Copies of the Barber alias Nynne book which was published in January 2015

have been sent to the Sussex and Kent county archives, libraries and the Society of Genealogists in London. - Anecdote:

© Geoffrey Barber 2015, 2019.

Citations

- [S104] Catharine Pullein, "Rotherfield: The Story of Some Wealden Manors", Courier, First Edition (1928).

Cyril Percy Knight

b. 25 December 1913, d. April 1999

Parents:

Father: Octavius Harry Knight b. 3 Apr 1879, d. 7 Feb 1959

Mother: Minnie Barber b. 10 Dec 1878, d. 1940

Mother: Minnie Barber b. 10 Dec 1878, d. 1940

Last Edited: 18 Dec 2023

- Birth*: Cyril Percy Knight was born on 25 December 1913 at Brighton, Sussex, EnglandB; Date of birth from GRO Deaths Index.1

- He was the son of Octavius Harry Knight and Minnie Barber.

- Occupation*: Cyril Percy Knight was a joiner in 1936.

- Marriage*: Cyril Percy Knight married Constance Mary Chilcott, daughter of George Chilcott, on 20 September 1936 at Brighton, Sussex, EnglandB, surname spelt CHILLCOTT.2